An elevator ride to the fourth floor of a New York City office building doesn't take very long, even in 1897, but there was enough time for sixty-four-year-old former real estate developer William Van Aken to contemplate his next move. Stepping quickly into the car, guided by a nameless, hardened accomplice recruited just that morning, he heard the elevator boy call out, "What floor, mister?" Van Aken replied enthusiastically, "Fourth-floor office of J.R. McPherson - I will see him if I have to wait all day. This thing has got to be settled!"

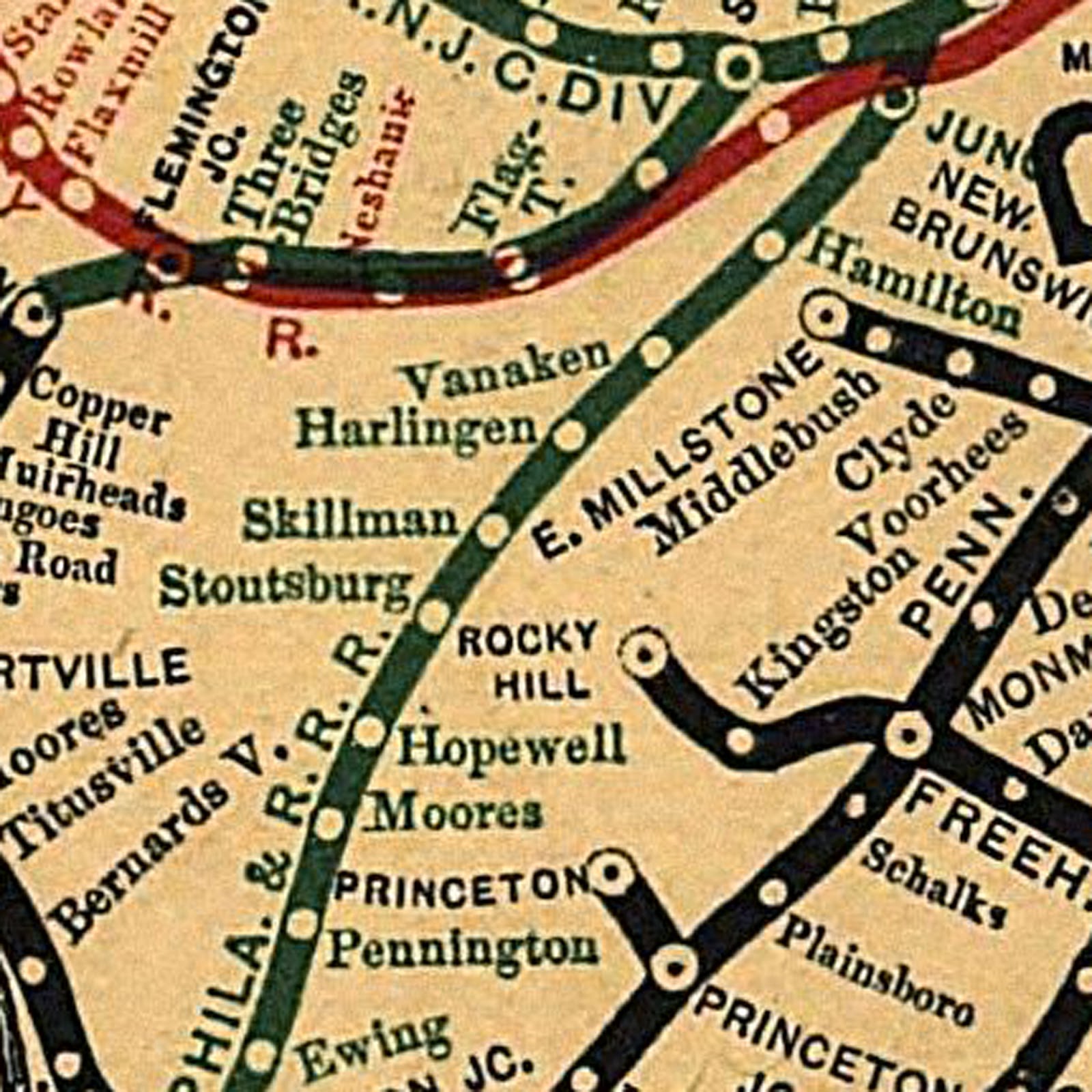

.jpg) |

| Illustration from the May 19, 1897 edition of the New York World |

Listening to the inner and outer doors clap shut, Van Aken thought back to his last meeting with the millionaire senator from New Jersey. In 1879, Van Aken proposed that McPherson purchase the approximately 800 acres of foreclosed property at Plainville, New Jersey, for the bargain price of $30,000, continue Van Aken's plan to create a small industrial city on the site, and split the profits 50-50.

McPherson did indeed purchase the land, and although he did not fulfill Van Aken's original scheme - opting instead to embark on a project to create a world-class dairy operation and estimable farming enterprise - wasn't it true that McPherson's Belle Mead Farm was an enormous success, and that Van Aken never saw a cent? Didn't the senator sell out in 1891 during his third term when he was being talked up for a presidential run? Weren't there profits aplenty? In any case, wasn't McPherson the president of the Western Stockyards Company? Surely he would like to settle the matter!

|

| Illustration from the May 19, 1897 edition of the New York Herald |

As the elevator boy announced, "Fourth Floor", Van Aken contemplated what his life had been like these past eighteen years. At first, he was active in many other land and business interests all across the country. But as the years passed, it seemed he couldn't catch a break. Even his most promising investment in the Kansas City Terminal was tied up in litigation. He was still wearing fine suits, but now they were noticeably ten years old. In the final indignity, he was nearly totally blind due to a botched cataract operation. For a while, his son sent him money from Chicago, but for the past eighteen months, he had been living at the modest Adams House Hotel at the corner of Gansevoort Square as a guest of the proprietor, an old friend.

With his companion urging him forward, Van Aken departed the elevator and swept right past McPherson's personal secretary and into the inner office. The startled former senator, frail even for a sixty-five-year-old, had no time to rise from his desk before Van Aken was put into a chair and pushed right up to McPherson, their knees almost touching. "I guess you know who I am and why I am here", stated Van Aken.

"That matter is tied up in the courts", replied McPherson, referring to the suit Van Aken had brought six months earlier to recover part, if not all, of the $280,000 he spent developing the Belle Mead property. "I refuse to enter into any further discussion".

"I am tired and sick of lawyers and courts. I'll have no more to do with courts". And, raising his voice now in anger, Van Aken continued, "I want this case settled without the courts!"

With that, Van Aken's accomplice shoved his master's chair abruptly forward so that the combatants' knees banged together. Leaning closer now to the feeble senator, the blind man breathed intensely, "If you won't settle it, then by God I will settle it!"

|

| Trial of William Van Aken as illustrated in the June 22, 1897, edition of the New York Herald |

Letting loose a rage that had been smoldering for years, Van Aken lunged across the desk and grabbed in his darkness for McPherson. The frightened McPherson was just able to dodge Van Aken's grasp and start towards the door leading to the outer office. Out of his chair now, reaching out in the barely distinguishable shadows, Van Aken sprang for his adversary. At the same moment, the brutish thug gave McPherson a shove, which landed him in Van Aken's arms.

They struggled at the doorway, Van Aken's left hand squeezing so tightly to the former senator's right wrist that he cried out in pain. "Now will you settle?" he questioned as he slid his right hand into his hip pocket and reached for a .44 caliber revolver,

By this time, McPherson's private secretary Edward Low had arrived from the anteroom and assessed the situation. The moment Van Aken's hand went into his pocket, Low's hand followed. The fearless secretary, the husband of the former senator's niece, managed to get his finger in between the trigger and the guard of the weapon, preventing the revolver from being discharged. The three struggled in the doorway while Van Aken's accomplice, realizing that the tide had turned, escaped out of the office and down the stairs.

Van Aken held fast to McPherson's wrist, as Low held fast to the revolver, the fighting lasting four or five minutes and spilling finally into the outer hallway. Low exhorted the senator to call out. "Help! Murder!" he shouted as the other fourth-floor tenants came out into the hallway. Just then, the elevator doors opened, and the building janitor appeared, delivering a mighty blow to the chin of Van Aken, causing him to at last release the gun, which was retrieved by Low.

Still holding McPherson's wrist, Van Aken began to curse, "You've ruined me, ruined me. And treated me like a dog!"

Five weeks later, at the trial for attempted murder, Van Aken's lawyer did a good job of showing there was no proof that his client went to McPherson's office that day to murder the former senator, or even to assault him, and in fact, did not even remove the revolver from his pocket. When Mr. Low testified that Van Aken and his accomplice appeared to be unprincipled men, the defense attorney saw an opening. "Did you ever know Mr. Van Aken to do anything so unprincipled as this, being a United States Senator, to speculate in stock certificates when their value would rise or fall according to his vote?", referring to the incident near the end of McPherson's third term when he was nearly laughed out of the Senate for explaining that a telegram authorizing stock transactions that he meant to throw away was accidentally left out and sent by one of his servants.

After this, the defense attorney asked for an immediate acquittal, which was granted - although Van Aken was still ordered to be held over for possession of an unlicensed firearm.