On May 4, 1909, Giulio Gatti-Casazza and Andreas Dippel - the co-managers of the New York Metropolitan Opera - sailed for Europe on their annual talent search. Before they left, the pair announced the singers they had already signed for the new season beginning in November, including the only singer up to that time who had not trained in Europe - a twenty-one-year-old soprano from South Branch, New Jersey named Anna Case.

|

| 25 May 1909, Butte Miner |

Although she had been singing professionally full-time for just over two years - and had been making a reputation as a unique talent at least since her July 4, 1908 appearance at the famous Ocean Grove Auditorium - this was the first time the national public had heard the name Anna Case.

|

| 12 May 1909 St. Louis Post-Dispatch |

Aside from being the first Metropolitan Opera singer with no European training, other now-familiar elements of Anna Case's story were promulgated by the press in those first weeks and months after Herr Dippel's announcement. Much was made of the fact that her father Peter Case was the village blacksmith at South Branch and that his daughter helped him in his shop, even shoeing horses on occasion.

|

| The blacksmith shop of Peter Case from a circa 1907 postcard. The house Anna Case grew up in is on the right. |

Before long, syndicated feature stories began to appear in the pages of newspapers across the country. Although most got the circumstances of the chance meeting between Director Dippel and the budding singer wrong - they met at her performance at Philadelphia's Bellevue-Stratford Hotel, not at a church in Plainfield - other parts of her story came to light. Readers were fascinated by the story of the early life of Anna Case - how she scrubbed floors and worked in the kitchens of her neighbors, sold soap door-to-door, drove a hansom cab for fares to and from the local train stations, and gave piano lessons for children in the evenings - a revolver tucked into her belt for protection on the country roads.

|

| 30 May 1909, St. Louis Post Dispatch |

In the first few years of her career with the opera, more aspects of the beginnings of Anna Case were revealed - how she borrowed seventy-five cents a week from the South Branch grocer so that she could take singing lessons from a Somerville music teacher, how she got a job playing the organ and leading the choir at the Neshanic Reformed Church, and then a job singing in the quartet at the First Presbyterian Church in Plainfield.

|

| 5 December 1909, San Francisco Examiner |

By the time she agreed to meet a photographer on the roof of one of the big newspaper buildings in New York to have her photo taken holding a blacksmith's hammer, the story of Anna Case was already well known. It's not unusual or surprising that the press - and the Metropolitan Opera - would engage in myth-building - in later years they managed to shave first one, then two years from her age in order to promote an ever-youthful prima donna. What is surprising is that in the case of Miss Case the stories were essentially true.

|

| 22 December 1912, Buffalo Sunday Morning News |

Unlike other New Jersey celebrities, past and present, whose connection to our state became more tenuous the more famous they became, Anna Case belongs to that group which includes Frankie Valli and Bruce Springsteen - singers for whom the New Jersey of their youth became an essential element of their larger-than-life stories.

|

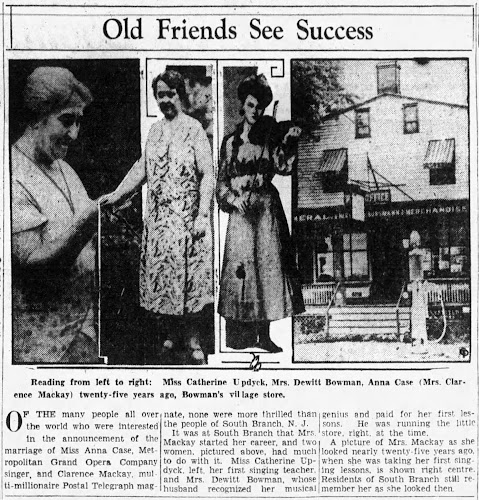

| 25 August 1931, Brooklyn Standard-Union |

But it wasn't only Anna Case's story which remained inextricably linked to New Jersey throughout her lifetime, but also Anna Case herself. After the death of her father in the 1920s, she repurchased her childhood home in South Branch and remodeled it as a home for her mother. After her mother's passing, Anna Case kept the home as a country retreat before gifting it to the South Branch Reformed Church in 1974 at the age of 86.

No comments:

Post a Comment